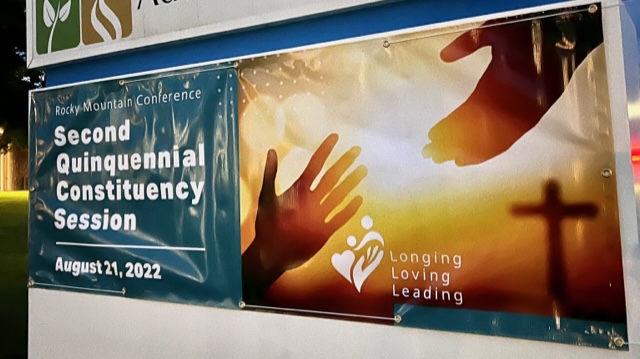

By Brenda Dickerson with Rajmund Dabrowski – Denver, Colorado … Delegates to the Rocky Mountain Conference of Seventh-day Adventists second quinquennial session met on Aug. 21, 2022, for the purpose of electing leadership, receiving reports, and conducting other church business. Five-hundred-ten registered delegates representing local Adventist churches in Wyoming, Colorado, and part of New Mexico convened at LifeSource Adventist Fellowship in Denver, Colorado, under the theme “Longing, Loving, Leading.”

After due consideration, delegates voted by a strong majority to elect Mic Thurber as president, Doug Inglish as vice president for administration, and Darin Gottfried as vice president for finance for the next five years.

Praise, prayers, and procedures

During the devotional time that followed the musical praise, conference president Mic Thurber explored the Longing, Loving, Leading theme by referencing Jesus’ words: “‘By this everyone will know that you are my disciples if you love one another.’ The quality and focus of our longings inform how well we love one another,” said Thurber.

His specific challenge to the delegates as local leaders was to “Be faithful and be alert for opportunities to speak into someone’s life…Let’s say gracious words that will bring hope, restoration, and grace.”

As the session was called to order, president Mic Thurber offered explanatory remarks regarding the procedures of the day. Thurber urged decorum and the following of standard procedures. “The purpose of procedures is to let the minority have their say, and to let the majority have their way,” said Thurber.

The General Conference Rules of Order, sixth edition, was followed diligently under the watchful eye of Darrell Huenergardt, MAUC legal counsel, who was voted by the delegates to serve as parliamentarian for the session.

Several motions made from the floor by delegates, passed, adding additional items to the day’s agenda including allowance for discussion of the composition of RMC’s Nominating Committee and Executive Committee, to be addressed in the bylaws. Other additional items were more representation from minority churches on committees and allocation of financial resources to Hispanic youth ministries.

One of the most celebrated votes was accepting nine new churches and companies established in 2017 into the sisterhood of RMC churches.

The auditor’s report was presented by Paula Aughenbaugh, representing the General Conference Auditing Service. Their unconsolidated financial statement received an “unmodified” opinion, the best possible opinion that can be given.

Election of officers and committees

A motion to refer the report for president back to the Nominating Committee was defeated by approximately a two-thirds majority. The vote for president was 71% in support of Mic Thurber to serve as president for the coming quinquennium. Following the vote Thurber said, “We are honored to serve, not by might, nor by power, but by the Spirit. Thank you so much for your trust.”

After 64% voted against sending back the report for vice president for administration, 68% of delegates voted in favor of Doug Inglish for vice president for administration. “Thank you for your confidence. I’d also like to say a word of thanks to my predecessor Eric Nelson for his guidance,” said Inglish.

Darrin Gottfried was elected by 97% to serve as vice president for finance. “This is a very exciting conference to work in. I’m looking forward to finding ways we can grow as a conference,” Gottfried said.

After a haystack lunch hosted by local Pathfinders, delegates resumed the business session by approving the Nominating Committee reports recommending names for the following committees: Constitution and Bylaws Committee, Executive Committee, Education Committee, and Property and Trust Committee.

Ordination of men and women pastors

Hubert J. Morel Jr., vice president of administration for the Mid-America Union Conference, gave introductory remarks prefacing the ordination discussion. Morel reminded delegates of the fact that the Adventist Church is comprised of nearly 22 million members around the globe. Yet we are all called to the same mission of spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ. Morel then gave some historical background from the Adventist Church’s actions in the 1920s to the 1970s regarding the role of women in gospel ministry. “What do we do in our own territory about this of women’s ordination?” Morel asked.

The motion brought to delegates was: “The Rocky Mountain Conference may submit names of all qualified men and women for ordination to the Mid-America Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists.”

Nine delegates immediately stood to speak at the “Against” microphone, while 13 lined up for the “Pro” microphone. Others joined both lines, but time did not allow for everyone to speak since the body voted against extending the time frame

In summary, the arguments focused on words and phrases such as equality, gender confusion, headship theology, church authority, the Holy Spirit’s calling on pastors, generational and cultural divides, financial ramifications, the role of missions, allowing women to attend seminary, the three angels’ messages in social equality, opposing the world church’s vote, following the voice of God, church levels and structure, competition, recognition, rejection, ordination at baptism, striking ordination completely, insubordination, angels tabulating the results of voting devices, Old Testament offerings, preaching for God, gender role clarification, circumcision as a rite, the message being sent to youth, compliance, rebellion and anarchy, biased presentations, fact versus opinion, divisions in the church, respect, women who followed Jesus, complementary roles, definition of ordination, biblical examples of “laying on of hands,” the role of women in ministry, definition of “harmony,” delegation of authority, fundamentalism, Ellen White, traditions, equal pay for equal work, policy vs doctrine, Theology of Ordination Study Committee, discrimination, God’s best choices for us, scriptural authority, variances (exceptions) to policy.

Fifty-nine percent of delegates voted in favor of the motion.

A lengthy discussion followed regarding protecting personal convictions toward women’s ordination and that they should not be used in a discriminatory manner for hiring, firing or prevention of promotion for employees within the Rocky Mountain Conference. The body voted to refer this to the RMC Executive Committee.

For Brooke Melendez, associate pastor from The Adventure Church in Greeley, Colorado, attending the RMC constituency session was her first in the conference. She remarked that August 21 “was a day I have been waiting for [for] seven years–since I became a pastor in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to be a part of it.”

She added, “however, I continue to hold heavy in my heart my female colleagues & friends in other conferences and unions who continue to serve in a different reality. I am praying and waiting with great anticipation for the day that I’m able to attend their ordination services and see them receive the full recognition from their church for what God has already called and ordained them to do.”

Bylaws discussion and changes

As delegates reviewed a 17-page-front-and-back document outlining the bylaws, several minor editorial changes were voted as a block. All changes to the bylaws require a two-thirds majority vote. Additional changes clarified wording and intent. Substantive changes were voted on individually. The wording regarding relationships between various levels of the Adventist Church was discussed several times throughout the day. Several items were referred to the bylaws committee for further revisions.

President Thurber thanked delegates for the consistent decorum exhibited by all who spoke, even as the hours passed.

Remarking on the “very full day” of deliberations, Dr. Mark Johnson, a delegate from Boulder, Colorado said that “attending the RMC Constituency Meeting this year was a bittersweet experience. It was nice to see old classmates and fellow church members from the past, but disturbing, and somewhat alarming, to find that our basic beliefs and views on truth have become so divergent. While the meeting was cordial and amicable, for the most part, the underlying tensions and religious zeal occasionally broke through. Unfortunately, as one delegate brought to our attention, the intensity seemed to be based on both theological interpretation and civic political fervor.”

Leaving the quinquennial meeting, Johnson commented that “the great challenge for the leaders will be holding the church together in some semblance of unity, given such fundamental diversity among the members.”

Samantha Nelson from Clark, Wyoming, commented on the length of the meeting. “I wish the meeting had not taken so very long and that some of the agenda items that were added could have been sent in advance to be addressed and dealt with prior to reaching the body for a vote. Many of them failed because there was so much going on and people were exhausted. All in all, things went well, and we have much work to do moving forward.”

That notwithstanding, random comments overheard in the church lobby as delegates were eager to go home, indicated that they seemed to be in a great mood and happy to be there. After all, each such convocation allows friends to meet friends whenever such events allow them to come together. “I wish we could meet more often,” one delegate from Colorado remarked.

Ron Price, a delegate from Farmington, New Mexico, summed up his experience at the session. He said, “I was well impressed with the overall tenor of the conversations, some of which verged on being debates. While many held strong values and beliefs, these seemed, for the most part, to be subjugated to the overreaching presence of love for our Lord and each other.”

–Brenda Dickerson is OUTLOOK editor and Rajmund Dabrowski is RMC communication director. Photos by Rajmund Dabrowski.