By Nathaniel Gamble

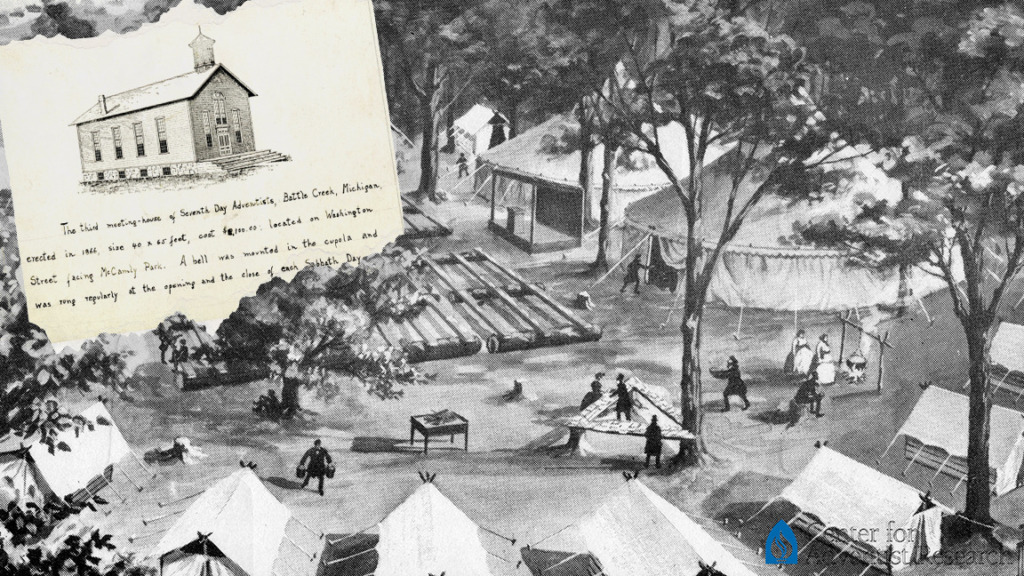

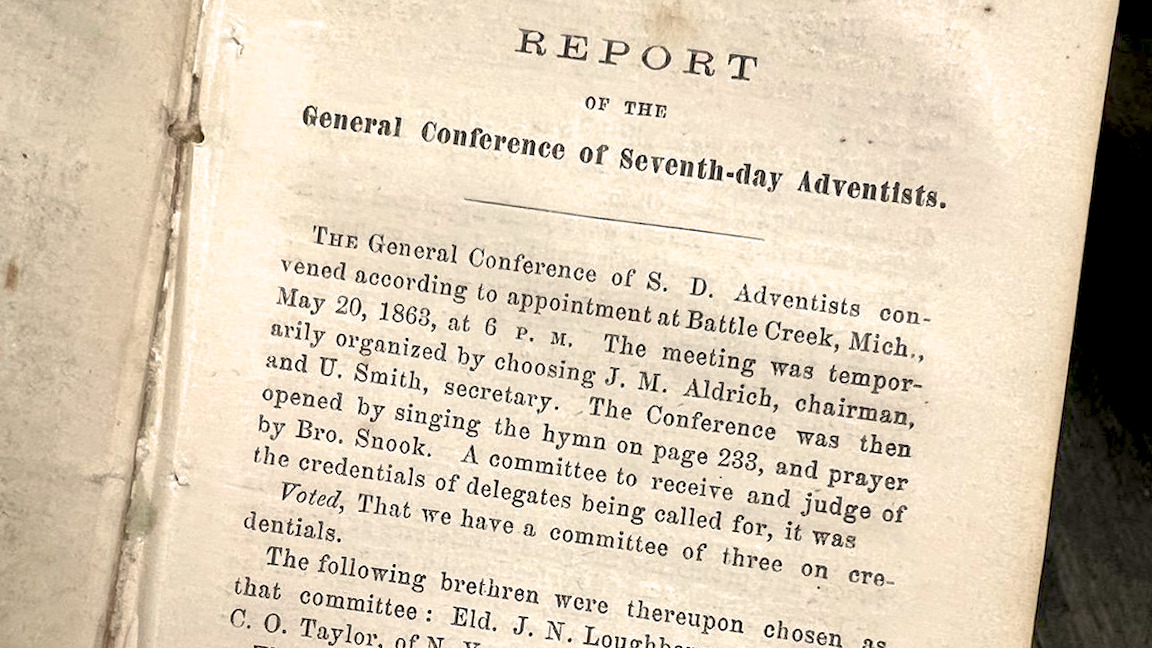

On May 21, 1863, the Seventh-day Adventist Church was officially organized at the denomination’s first General Conference Session in Battle Creek, Michigan. Such a date makes May 21, 2023, the 160th anniversary of that momentous occasion. There have always been three traits which define our denomination: a mission from shared, central beliefs; external pressures as the primary cause for ongoing theological, organizational, and liturgical development; and the use of pragmatism to solve our problems.

The Adventists who came out of the Millerite Movement and eventually formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church were a wild bunch of people and held a variety of political, economic, and religious convictions. Divisive issues we struggle with today were also faced by the nascent Advent believers: the place of women (and men!) in the church, multiple ethnicities and multiculturalism, church governance, the sequence of end time events, increased technology, and what it means to be human.

The early Adventists realized they needed missional unity that only God could give, which ultimately came in the form of convictions from the Sabbath and Sanctuary Conferences of 1846-1848: the seventh-day Sabbath, Jesus’ second coming, death as sleep, the heavenly sanctuary as God’s solution for evil, and the presence of the Holy Spirit and his gifts in the church (especially the gift of prophecy). The Seventh-day Adventist Church built on these five pillar doctrines as the key to its missional unity and identity.

But like other Christian groups, the Seventh-day Adventist Church has usually been slow to make necessary changes to its administration, theology, and worship, often being pushed by external factors into these adjustments. Missional success forced Adventists to develop an institutional framework, first by actually creating a denomination to further evangelism, and later by creating unions and divisions to make administration more manageable.

Likewise, early Adventists remained noncommittal about the nature of God and tolerated Trinitarian, Arian, Unitarian, and Deist views among their members. But the influence of Adventist revivals in the late nineteenth century, the 1888 General Conference Session on righteousness by faith, and the Bible studies on Jesus and the Holy Spirit throughout the 1890s helped convince the Seventh-day Adventist Church that a Trinitarian view of the Godhead made the most sense of their mission and message.

And the wide variety of worship experiences among early Adventists, with some services being cold and sterile and others including shouting, clapping, and stomping, resulted in the publication of hymnbooks and resources for baptismal preparation, as well as conversations about the order of a worship service that continue to be felt in “contemporary” and “traditional” worship styles in the twenty-first century.

Due to both our God-given mission and these external factors, the Seventh-day Adventist Church has often been pragmatic about solving problems. For instance, the Seventh-day Adventist Church leaves the matter of pacifism or military service up to the individual conscience and simply asks, “Which option helps you follow Jesus better?” Similarly, the denomination has thought a lot about the practical aspects of pastoral ministry and what God calls a person to do, but it has never been very interested in theological questions about the difference between clergy and laity, the role of sacraments in the Christian life, or the relationship between baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and ordination.

Amidst the ongoing challenge of racism for every Christian denomination, the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s historical involvement in abolition and example of incorporating racial diversity into the denomination continues to serve as an inspiration for current church members to emulate. While our stand against racism was more full-throated in the past than it sometimes is in the present, our ongoing method of addressing racism has made us one of the most racially diverse denominations in the world. The same pragmatism is present in our treatment of creation and evolution, gender and ordination, worship styles, Christian behavior, sex and sexuality, human trafficking, work and money, and a thousand other concerns.

The result of this menagerie has been the birth of a denomination that serves as a spiritual family with collective beliefs and a common life purpose. Wherever you go and wherever you’ve been as a Seventh-day Adventist, you always belong to a people and you always have a spiritual home that is continually being healed by God. And this means you’re always a representative of the wildly exciting—and slightly eccentric—denomination known as the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

1863, your church was born! Today, you are a consequential part of it. And God leads!

—Nathaniel Gamble is the RMC religious liberty director. Photos courtesy of Michael Campbell and Center for Adventist Research.