Words of gratitude for the faithfulness of church members were expressed as part of a report that since August 31, 2019 tithe is up 10.72%. George Crumley, RMC VP for finance, reported to the Rocky Mountain Conference Executive Committee, October 8, that, “the strong tithe performance is related to a strong tithe windfall year which we are thankful for. The other reason it is strong is because we have an extra Sabbath through August this year as compared to last year.”

In his President’s Report, Ed Barnett shared financial challenges facing several entities in the Mid-American Union Conference. “We are grateful to report that RMC finances are in the positive. Not all conferences in our Union can report that. The Dakota Conference voted to withdraw a subsidy given to Union College due of their economic downturn, effecting tithes and offerings in that region. In my view, such an action would be detrimental to the future of the college,” Barnett commented. “Anything, but not Adventist education,” he added.

Barnett said the “it always hurts when our sister Conferences are struggling. We need to keep them in our prayers.”

Reporting to the committee, Roy Ryan, chairman of the Auditing Committee of the conference said the “2018 Audit Committee report is a good report.” The General Conference Auditing Service auditors had hardly a point to make and RMC received an unmodified opinion issued for the finances of the conference. “This is the best opinion that can be received,” he said.

Crumley also shared that the operations of the Adventist Book Center continue to wind down with a scheduled closure by December 31, 2019.

The committee was informed by Eric Nelson, RMC VP for administration, about some staff changes at the RMC office. Linda Reece has taken a call to serve in the Georgia-Cumberland conference, with Chanelle Watson taking on the insurance/loss control portion of this position. Another part time individual will take the responsibility of the auditing. This will be announced later. At present the office has reduced 2.5 full time positions.

The meeting concluded receiving three departmental reports. The Trust Department report by Doug Inglish included information about partnering with the Western Adventist Foundation in closing out a number of the matured trusts. This has made significant savings for the Trust Department. Recently the department has received a certification of full accreditation rating of A-2. That is a top rating of A for a period of 2 years.

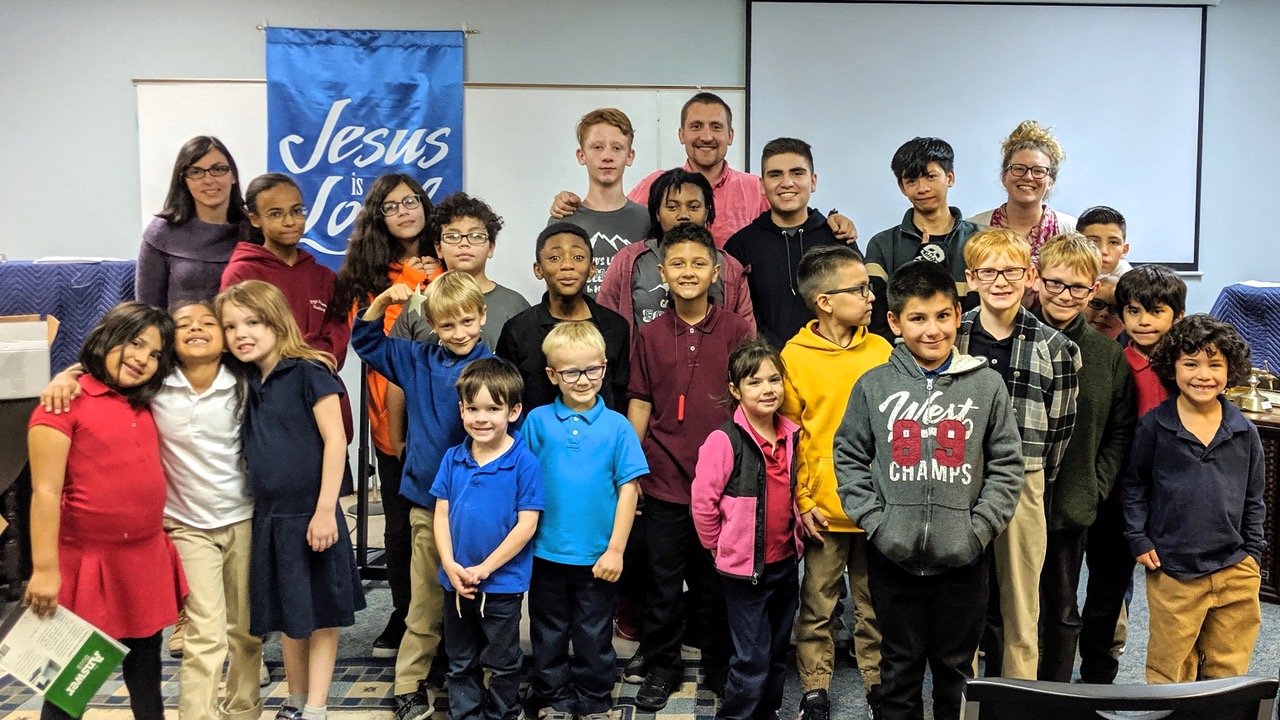

Kiefer Dooley reported on behalf of the Youth Department that there were 634 campers at our 2019 summer camp, and included 71 staff, six volunteers, 11 nurses, and eight pastors. During the camps eight young people and one staff member were baptized. ‘We rejoice that there were 400 expressions of commitment to Christ that took place during camp season,” Kiefer said.

Mickey Mallory, RMC ministerial director, reported about Lay Pastor Training Pastor Nate Skaife, from Grand Junction, led a lay pastor training-module in Denver and will soon lead one in Grand Junction. This training occurs in three sessions per year. Those who attended expressed the positive benefit that they received and look forward to implementing it in their churches, Mallory commented.

The next meeting of the committee is scheduled for December 10.

—RMCNews; photo by Rajmund Dabrowski