Navajo News Team – Farmington, New Mexico … “We had fun.” “The food was delicious.” “The staff are friendly and helpful.” “It’s a nice event, thank you.” “Thank you so much for what this mission does. Always caring and loving.” These are some of the comments from the community members who attended the 2024 Annual Christmas Fiesta and Propane Give-away at La Vida Mission* (LVM) in Farmington, New Mexico, December 17.

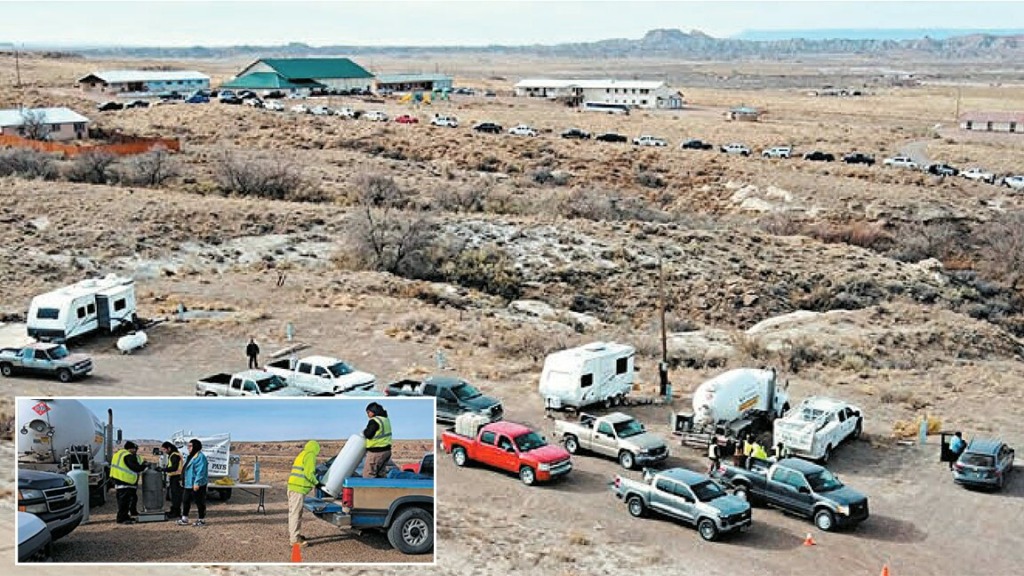

The event officially started when the La Vida Mission students and staff gathered in the gym at 9:00 a.m. for a morning worship service led by Emily Lowe, LVM school alumna, and students from the Boys’ Dorm. Propane refill services were scheduled to begin at 10:00 a.m., but trucks lined up for as early as 6:30 a.m. They kept coming and filled the whole Country Road 7730 up to the Mission.

As attendees entered the gym for the main event, they were greeted at a welcome booth and given a wool blanket, Ellen G. White’s book Steps to Christ, other spiritual literature, and a raffle ticket for tons of door prizes from LVM donors. Other activities and services that were offered were a “Free Flea Market” with all-day refreshments and a Christmas meal. Christmas fry bread was provided by Renita and Reva Juan, members of the La Vida Mission Seventh-day Adventist Church, and many loaves of bread and assorted bakery products were provided compliments of the local Bimbo Bakeries.

At 11:30 a.m., all activities in the gym were stopped and everyone was invited to take a seat for the Christmas messages and prayers delivered by LVM staff including Dorie Panganiban, Danita Ray, and Kim Ellis. “We reminded everyone that, while we offer them all kinds of gifts, we always want to offer and share the greatest gift of all, Jesus,” remarked one of the event’s organizers. “We let them know that Jesus can change our lives and make it better and encouraged everyone to be close to God and prepare for the second Christmas, the second coming of Jesus, which is very soon.”

The message and prayers were followed by the Christmas fellowship lunch with continued raffle ticket drawings for door prizes. Students and staff were still not tired after all the events of the day and lingered for more games after the gym was cleaned, led by LVM staff Beth Fugoso-Panganiban, Cielo Domino, and Glet Franche.

“This one community event of the Mission for our native family is a corporate effort of all La Vida Mission staff, with some of our donors, designed to continue to share the love of Jesus to the Diné, the Navajo people, and everyone around us. Please continue to include us in your prayers that we may always shine for Him and spread His love to everyone. Thank you from Dorie, with VJ Panganiban and Beth, co-outreach directors, who directed this event.”

* La Vida Mission is a supporting ministry of the Seventh-day Adventist Church but is not affiliated with the Rocky Mountain Conference of Seventh-day Adventists.

—Navajo News Team. Photos supplied.