The years of our lives are about threescore and ten, which is about 70 years. 80, if you are strong enough to last … Psalm 90:10 (Authors Translation).

Psalm 90:10 goes on to explain that most of this life is going to be labor and trouble, and then, essentially, we die.

This is true of all of us, even Adventists. While we well may eke out a few more years due to our lifestyle choices, we still are not guaranteed too much time on this earth. It is but a blip in the wink that is eternity. And yet, we find so much meaning in living those 70-80 years. I have often wondered if being an Adventist, and believing as we do, adds more life to our years than just years to our lives.

I was recently in Jakarta, Indonesia, and was struck by the sheer mass of humanity that roamed its streets. Something close to 34 million people live in Jakarta, the second largest city in the world as of this writing. It was shocking in its size and scope. Thirty-four million people and not many Adventists are counted among its people. Does this mean that our message does not impact that world? Does it mean that these tenets from which we live either fall on deaf ears or are no longer relevant to a population such as Jakarta? Of course, most of the populace is Muslim, but do we have nothing to offer those from a different tradition?

These musings have led me to think further about whether or not these beliefs that we hold make an impact even around us. We believe them so fervently, and they mean so much to us, but statistically, those concentric circles that cascade out from us in the form of influence don’t always seem to make a significant impact. We rarely see a population hungry for what we have to offer through our faith tradition. Does that mean our tradition is bereft of meaning and value, or is something else happening?

Does our orthodoxy fall on deaf ears? Or does it not fall anywhere?

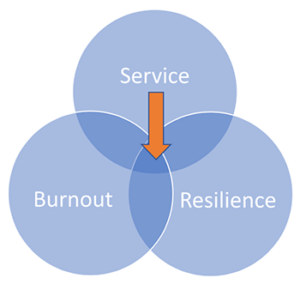

It is a question of orientation in some cases. How are we oriented in our faith lives, and what is it that we are offering a hurt, broken, and breaking world? Are they hungry for the doctrinal statements that make up our orthodox beliefs or something else? And if it is something else, what would that be? Would it be the orthopraxy that we have to offer? The idea that our beliefs lead to a behavior that is attractive and helpful to someone else. Our orthodoxy should be impacting our orthopraxy (right doing), but is there something else that those hurting in this world crave?

Perhaps they are looking for our orthopathy or our right hearts. We may need to begin there. So, we have to ask a particular question: Where is the orientation of your heart? In what direction does it point?

I was recently preaching on Revelation 4 and the glimpse of the throne room of God. If you remember the text, you remember that it is a pretty amazing scene, with the four living creatures, the 24 elders, and the seraphim/cherubim that had been mentioned before in both Ezekiel and Isaiah.

At once I was in the Spirit, and there before me was

a throne in heaven with someone sitting on it. And the

one who sat there had the appearance of jasper and

ruby. A rainbow that shone like an emerald encircled

the throne. Surrounding the throne were twenty-four

other thrones, and seated on them were twenty-four

elders. They were dressed in white and had crowns of

gold on their heads. From the throne came flashes of

lightning, rumblings, and peals of thunder. In front of

the throne, seven lamps were blazing. These are the seven

spirits of God. Also, in front of the throne there was what

looked like a sea of glass, clear as crystal.

In the center, around the throne, were four living creatures,

and they were covered with eyes, in front and in back. The

first living creature was like a lion, the second was like

an ox, the third had a face like a man, the fourth was like

a flying eagle. Each of the four living creatures had six

wings and was covered with eyes all around, even under

its wings. Day and night they never stop saying:

“Holy, holy, holy

is the Lord God Almighty,”

who was, and is, and is to come.

(Revelation 4:2-8)

As the text continues, we see that when the four living creatures who are the worship leaders in this text sing these praises to God, the 24 elders lay down their crowns and worship God. We see that the 24 elders knew their place, firmly planted under the rule of Jesus.

But what strikes me as most compelling in this text is the orientation of everyone in the room. They are all focused and oriented on the Throne of God. Their focus is on praising Jesus, and they commit themselves to this all day, every day. Do we have such an orientation and focus on our lives? If we did, would all that we believe be received differently by those around us?

The orientation of our hearts makes a difference in the trajectory of our lives.

I was picking up my son the other day from school, and I noticed he was hanging out in a large crowd. A test I do when I see a crowd is to try to notice how the crowd is oriented. I look at people’s feet and see which way they are oriented. This particular day, all toes seemed to point at my son, who was holding court! At that moment, he seemed to be the organizing principle for that set of kids in that group. Of course, as a dad, I was proud that he seemed so popular. But my question for him was simply this: “What were you talking about?”

While he was telling a joke, we can orient our lives, much like in the throne room, toward Jesus and then allow Him to be the most compelling person in any room.

So, to answer the question posed at the beginning of the article, does what we believe have any bearing on our lives, on our witness to others? The answer is a resounding yes but in the right order. First, we need our orthopathy and hearts to be in the right place. Then, our orthopraxy matters to people as they know we care for them, and they see that with our actions. Lastly, as they trust and respect who we are and how we live, they see the beneficence of believing those things we believe to be orthodox. When we flip this order, we create people who know the right things but often don’t feel like they belong, don’t practice what they have assented to be accurate, and cannot be trusted to have their hearts in the right orientation.

One last note on orientation. I have often said from the Crosswalk pulpit that evangelism is not a program or an event but the orientation of the congregation’s heart. And I continue to believe this to be true. Our churches, our faith, and the Kingdom of God grow through the tireless efforts of every person who calls themselves a Christian as they invite, share, and walk with others in their lives toward an understanding of Jesus. This has proven to be true as we have grown churches throughout the U.S. and beyond over the years. As a congregation engages in inviting those they care about to church, with people who have the orientation we have been speaking about, we see the Kingdom and the churches grow.

So, I would admonish you to continue to learn, grow, and believe. At the same time, check your orientation, know where your toes are pointed, and live in that trajectory.

Dr. Tim Gillespie is lead pastor of Crosswalk Church in Redlands, California. Email him at: [email protected]